3.3 Increasing and Decreasing Functions

Our study of “nice” functions in this chapter has so far focused on individual points: points where is maximal/minimal, points where or does not exist, and points where is the average rate of change of on some interval.

In this section we begin to study how functions behave between special points; we begin studying in more detail the shape of their graphs.

We start with an intuitive concept. Given the graph in Figure 3.3.1, where would you say the function is increasing? Decreasing? Even though we have not defined these terms mathematically, one likely answered that is increasing when and decreasing when . We formally define these terms here.

Definition 3.3.1 Increasing and Decreasing Functions

Let be a function defined on an interval .

-

(a)

is increasing on if for every in , .

-

(b)

is decreasing on if for every in , .

A function is strictly increasing when in implies , with a similar definition holding for strictly decreasing.

Informally, a function is increasing if as gets larger (i.e., looking left to right) gets larger.

Our interest lies in finding intervals in the domain of on which is either increasing or decreasing. Such information should seem useful. For instance, if describes the speed of an object, we might want to know when the speed was increasing or decreasing (i.e., when the object was accelerating vs. decelerating). If describes the population of a city, we should be interested in when the population is growing or declining.

There is a nice relationship between the sign of on some interval and whether is increasing or decreasing on that interval.

First, suppose that is differentiable and increasing on the interval . Then for any c in (a, b) we have

because for small . Thus for any in .

Conversely, suppose for all in . Then for any in , is continuous on and differentiable on . The Mean Value Theorem (Theorem 3.2.1) then implies that there is a in such that because and . Therefore . This means is increasing on .

We’ve now shown that for any differentiable on , is increasing on if and only if for all in . Using the same arguments we could show is decreasing on if and only if for all in . The following Theorem is now an immediate consequence.

Theorem 3.3.1 Test For Increasing/Decreasing Functions

Let be a continuous function on and differentiable on .

-

(a)

If for all in , then is increasing on .

-

(b)

If for all in , then is decreasing on .

-

(c)

If for all in , then is constant on .

Suppose and are in where and . Then there must be some number between and with . If is continuous on , this is an immediate consequence of the Intermediate Value Theorem. Even if isn’t continuous, such a must exist as a consequence of Darboux’s Theorem. (For a special case of this theorem see Exercise 39..) In either case, this leads us to the following method for finding intervals on which a function is increasing or decreasing.

Key Idea 3.3.1 Finding Intervals on which is Increasing or Decreasing

Let be a continuous function on an interval I. To find intervals on which is increasing and decreasing:

-

(a)

Find the critical points of . That is, find all in where or is not defined.

-

(b)

Use the critical points to divide into subintervals.

-

(c)

Pick any point in each subinterval, and find the sign of .

-

(a)

If , then is increasing on that subinterval.

-

(b)

If , then is decreasing on that subinterval.

-

(a)

Watch the video:

Finding Intervals of Increase / Decrease Local Max / Mins from https://youtu.be/-W4d0qFzyQY

We demonstrate using Key Idea 3.3.1 in the following example.

Example 3.3.1 Finding intervals of increasing/decreasing

Let . Find intervals on which is increasing or decreasing.

SolutionUsing Key Idea 3.3.1, we first find the critical points of . We have , so when and when . We see that is never undefined.

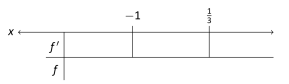

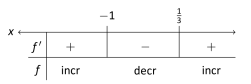

Since an interval was not specified for us to consider, we consider the entire domain of which is . We thus break the whole real line into three subintervals based on the two critical points we just found: , and . This is shown in the following sign chart.

We now pick a value in each subinterval and find the sign of . All we care about is the sign, so we do not actually have to fully compute ; pick “nice” values that make this simple.

- Subinterval 1,

-

: We (arbitrarily) pick . We can compute directly: . We conclude that is increasing on .

Note we can arrive at the same conclusion without computation. For instance, we could choose . The first term in , i.e., is clearly positive and very large. The other terms are small in comparison, so we know . All we need is the sign.

- Subinterval 2,

-

: We pick since that value seems easy to deal with and note that . We conclude is decreasing on .

- Subinterval 3,

-

: Pick an arbitrarily large value for and note that . We conclude that is increasing on and use all of our information to complete our sign chart.

We can verify our calculations by considering Figure 3.3.3, where we have graphed and . Note how when is increasing and when is decreasing.

One is justified in wondering why so much work is done when the graph seems to make the intervals very clear. We give three reasons why the above work is worthwhile.

First, the points at which switches from increasing to decreasing are not precisely known given a graph. The graph shows us something significant happens near and , but we cannot determine exactly where from the graph.

One could argue that just finding critical points is important; once we know the significant points are and , the graph shows the increasing/decreasing traits just fine. That is true. However, the technique prescribed here helps reinforce the relationship between increasing/decreasing and the sign of . Once mastery of this concept (and several others) is obtained, one finds that either (a) just the critical points and values are computed and the graph shows all else that is desired, or (b) a graph is never produced, because determining increasing/decreasing using is straightforward and the graph is unnecessary. So our second reason why the above work is worthwhile is this: once mastery of a subject is gained, one has options for finding needed information. We are working to develop mastery.

Finally, our third reason: many problems we face “in the real world” are very complex. Solutions are tractable only through the use of computers to do many calculations for us. Computers do not solve problems “on their own,” however; they need to be taught (i.e., programmed) to do the right things. It would be beneficial to give a function to a computer and have it return maximum and minimum values, intervals on which the function is increasing and decreasing, the locations of relative maxima, etc. The work that we are doing here is easily programmable. It is hard to teach a computer to “look at the graph and see if it is going up or down.” It is easy to teach a computer to “determine if a number is greater than or less than 0.”

In Section 3.1 we learned the definition of relative maxima and minima and found that they occur at critical points. We are now learning that functions can switch from increasing to decreasing (and vice-versa) at critical points. This new understanding of increasing and decreasing creates a great method of determining whether a critical point corresponds to a maximum, minimum, or neither. Imagine a function increasing until a critical point at , after which it decreases. A quick sketch helps confirm that must be a relative maximum. A similar statement can be made for relative minimums, see Figure 3.3.4. We formalize this concept in a theorem.

Theorem 3.3.2 First Derivative Test

Suppose that is continuous on an open interval containing , differentiable on an open interval containing except possibly at , and is a critical point of . Then

-

(a)

If the sign of switches from positive to negative at , then is a relative maximum of .

-

(b)

If the sign of switches from negative to positive at , then is a relative minimum of .

-

(c)

If the sign of is positive before and after , then is not a relative extrema of .

-

(d)

If the sign of is negative before and after , then is not a relative extrema of .

Example 3.3.2 Using the First Derivative Test

Find the intervals on which is increasing and decreasing, and use the First Derivative Test to determine the relative extrema of , where

SolutionWe start by noting the domain of : . Key Idea 3.3.1 describes how to find intervals where is increasing and decreasing when the domain of is an interval. Since the domain of in this example is the union of two intervals, we apply the techniques of Key Idea 3.3.1 to both intervals of the domain of .

Since is not defined at , the increasing/decreasing nature of could switch at this value. We do not formally consider to be a critical point of , but we will include it in our list of critical points that we find next.

Using the Quotient Rule, we find

We need to find the critical points of ; we want to know when and when is not defined. That latter is straightforward: when the denominator of is 0, is undefined. That occurs when , which we’ve already recognized as an important value.

when the numerator of is 0. That occurs when ; i.e., when .

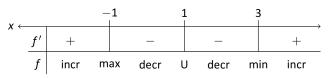

We have found that has two critical points, , and at something important might also happen. These three numbers divide the real number line into 4 subintervals:

Pick a number from each subinterval and test the sign of at to determine whether is increasing or decreasing on that interval. Again, we do well to avoid complicated computations; notice that the denominator of is always positive so we can ignore it during our work.

- Interval 1,

-

: Choosing a very small number (i.e., a negative number with a large magnitude) returns in the numerator of ; that will be positive. Hence is increasing on .

- Interval 2,

-

: Choosing 0 seems simple: . We conclude is decreasing on .

- Interval 3,

-

: Choosing 2 seems simple: . Again, is decreasing.

- Interval 4,

-

: Choosing a very large number from this subinterval will give a positive numerator and (of course) a positive denominator. So is increasing on .

In summary, is increasing on and and is decreasing on and . Since at , the sign of switched from positive to negative, Theorem 3.3.2 states that is a relative maximum of . At , the sign of switched from negative to positive, meaning is a relative minimum. At , is not defined, so there is no relative extrema at .

This is summarized in the number line shown above. Also, Figure 3.3.5 shows a graph of , confirming our calculations. This figure also shows , again demonstrating that is increasing when and decreasing when .

One is often tempted to think that functions always alternate “increasing, decreasing, increasing, decreasing, …” around critical points. Our previous example demonstrated that this is not always the case. While was not technically a critical point, it was an important value we needed to consider. We found that was decreasing on “both sides of .”

Example 3.3.3 Using the First Derivative Test

Find the intervals on which is increasing and decreasing and identify the relative extrema.

SolutionWe again start with taking derivatives. Since we know we want to solve , we will do some algebra after taking derivatives.

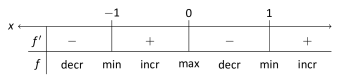

This derivation of shows that when and is not defined when . Thus we have 3 critical points, breaking the number line into 4 subintervals: , , , and .

- Interval 1,

-

: We choose ; we can easily verify that . So is decreasing on .

- Interval 2,

-

: Choose . Once more we practice finding the sign of without computing an actual value. We have ; find the sign of each of the three terms.

We have a “negative negative positive” giving a positive number; is increasing on .

- Interval 3,

-

: We do a similar sign analysis as before, using in .

We have 2 positive factors and one negative factor; and so is decreasing on .

- Interval 4,

-

: Similar work to that done for the other three intervals shows that on , so is increasing on . We can now put all this information into a chart.

We conclude by stating that is increasing on and and decreasing on and . The sign of changes from negative to positive around and , meaning by Theorem 3.3.2 that and are relative minima of . As the sign of changes from positive to negative at , we have a relative maximum at . Figure 3.3.6 shows a graph of , confirming our result. We also graph , highlighting once more that is increasing when and is decreasing when .

We examine one more example.

Example 3.3.4 Using the First Derivative Test with Trigonometry

Find the intervals on which is increasing and decreasing and find the relative extrema on the interval .

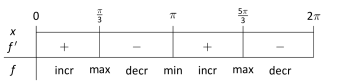

SolutionWe see that . Therefore, when . This breaks our number line into four intervals.

- Interval 1,

-

: We choose , and see that and are both positive. Therefore, .

- Interval 2,

-

: When , is positive, but is negative. Therefore, .

- Interval 3,

-

: When , and are both negative. Therefore, .

- Interval 4,

-

: When , and so that . We summarize this information in a chart.

This means that is increasing on and and decreasing on and , so that the relative maxima are and and the relative minimum is . (The values and would also be relative minima, but relative extrema are not allowed to occur at the endpoints of an interval.)

We have seen how the first derivative of a function helps determine when the function is going “up” or “down.” In the next section, we will see how the second derivative helps determine how the graph of a function curves.

Exercises 3.3

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

In your own words describe what it means for a function to be increasing.

-

2.

What does a decreasing function “look like”?

-

3.

Sketch a graph of a function on that is increasing but not strictly increasing.

-

4.

Give an example of a function describing a situation where it is “bad” to be increasing and “good” to be decreasing.

-

5.

T/F: Functions always switch from increasing to decreasing, or decreasing to increasing, at critical points.

-

6.

A function has derivative , where for all . Is increasing, decreasing, or can we not tell from the given information?

Problems

-

7.

Given the graph of , identify the intervals of increasing and decreasing as well as the coordinates of the relative extrema.

-

8.

Given the graph of , identify the intervals of increasing and decreasing as well as the coordinates of the relative extrema.

-

9.

Given the graph of , identify the intervals of increasing and decreasing as well as the coordinates of the relative extrema.

-

10.

Given the graph of , identify the intervals of increasing and decreasing as well as the coordinates of the relative extrema.

In Exercises 11–18., a function is given.

-

(a)

Compute .

-

(b)

Graph and on the same axes (using technology is permitted) and verify Theorem 3.3.1.

-

11.

-

12.

-

13.

-

14.

-

15.

-

16.

-

17.

-

18.

In Exercises 19–38., a function is given.

-

(a)

Give the domain of .

-

(b)

Find the critical numbers of .

-

(c)

Create a number line to determine the intervals on which is increasing and decreasing.

-

(d)

Use the First Derivative Test to determine whether each critical point corresponds to a relative maximum, minimum, or neither.

-

19.

-

20.

-

21.

-

22.

-

23.

-

24.

-

25.

-

26.

-

27.

on .

-

28.

-

29.

on

-

30.

on

-

31.

-

32.

-

33.

-

34.

on

-

35.

-

36.

-

37.

on

-

38.

-

39.

A special case of Darboux’s Theorem. Suppose is differentiable on the open interval . Suppose and belong to the interval with . Show that if and have opposite signs then there is an in the interval such that . (This statement would follow from the Intermediate Value Theorem if were continuous on but we are not assuming is continuous here.)

Review

-

40.

Consider on ; find guaranteed by the Mean Value Theorem.

-

41.

Consider on ; find guaranteed by the Mean Value Theorem.