3.4 Concavity and the Second Derivative

Our study of “nice” functions continues. The previous section showed how the first derivative of a function, , can relay important information about . We now apply the same technique to itself, and learn what this tells us about .

The key to studying is to consider its derivative, namely , which is the second derivative of . When , is increasing. When , is decreasing. As with , has relative maxima and minima where or is undefined.

This section explores how knowing information about gives information about .

Concavity

We begin with a definition, then explore its meaning.

Definition 3.4.1 Concave Up and Concave Down

Let be differentiable on an interval . The graph of is concave up on if is increasing. The graph of is concave down on if is decreasing. If is constant then the graph of is said to have no concavity.

Geometrically, a function is concave up if its graph lies above its tangent lines, so that it curves upward. A function is concave down if its graph lies below its tangent lines, so that it curves downward.

The graph of a function is concave up when is increasing. That means as one looks at a concave up graph from left to right, the slopes of the tangent lines will be increasing. Consider Figure 3.4.1(a), where a concave up graph is shown along with some tangent lines. Notice how the tangent line on the left is steep, downward, corresponding to a small value of . On the right, the tangent line is steep, upward, corresponding to a large value of .

If a function is decreasing and concave up, then its rate of decrease is slowing; it is “leveling off.” If the function is increasing and concave up, then the rate of increase is increasing. The function is increasing at a faster and faster rate.

Now consider a function which is concave down. We essentially repeat the above paragraphs with slight variation.

The graph of a function is concave down when is decreasing. That means as one looks at a concave down graph from left to right, the slopes of the tangent lines will be decreasing. Consider Figure 3.4.1(b), where a concave down graph is shown along with some tangent lines. Notice how the tangent line on the left is steep, upward, corresponding to a large value of . On the right, the tangent line is steep, downward, corresponding to a small value of .

If a function is increasing and concave down, then its rate of increase is slowing; it is “leveling off.” If the function is decreasing and concave down, then the rate of decrease is decreasing. The function is decreasing at a faster and faster rate.

Our definition of concave up and concave down is given in terms of when the first derivative is increasing or decreasing. We can apply the results of the previous section and to find intervals on which a graph is concave up or down. That is, we recognize that is increasing when , etc.

Theorem 3.4.1 Test for Concavity

Let be twice differentiable on an interval . The graph of is concave up if on , and is concave down if on .

If knowing where a graph is concave up/down is important, it makes sense that the places where the graph changes from one to the other is also important. This leads us to a definition.

Definition 3.4.2 Point of Inflection

A point of inflection is a point on the graph of at which the concavity of changes.

Figure 3.4.2 shows a graph of a function with inflection points labeled.

If the concavity of changes at a point , then is changing from increasing to decreasing (or, decreasing to increasing) at . That means that the sign of is changing from positive to negative (or, negative to positive) at . This leads to the following theorem.

Theorem 3.4.2 Points of Inflection

If is a point of inflection on the graph of , then either or is not defined at .

We have identified the concepts of concavity and points of inflection. It is now time to practice using these concepts; given a function, we should be able to find its points of inflection and identify intervals on which it is concave up or down. We do so in the following examples.

Watch the video:

Finding Local Maximums/Minimums — Second Derivative Test from https://youtu.be/QtXCIxB6kW8

Example 3.4.1 Finding intervals of concave up/down, inflection points

Let . Find the inflection points of and the intervals on which it is concave up/down.

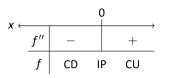

SolutionWe start by finding and . To find the inflection points, we use Theorem 3.4.2 and find where or where is undefined. We find is always defined, and is 0 only when . So the point is the only possible point of inflection.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3.4.3: A number line determining the concavity of and a graph of used in Example 3.4.1.

Λ

(a)

(b)

Figure 3.4.3: A number line determining the concavity of and a graph of used in Example 3.4.1.

Λ

This possible inflection point divides the real line into two intervals, and . We use a process similar to the one used in the previous section to determine increasing/decreasing. Pick any ; so is concave down on . Pick any ; so is concave up on . Since the concavity changes at , the point is an inflection point.

The number line in Figure 3.4.3(a) illustrates the process of determining concavity (to save space, we will abbreviate “concave down”, “concave up”, and “inflection point” to “CD”, “CU”, and “IP”, respectively). Figure 3.4.3(b) shows a graph of and , confirming our results. Notice how is concave down precisely when and concave up when .

Example 3.4.2 Finding intervals of concave up/down, inflection points

Let . Find the inflection points of and the intervals on which it is concave up/down.

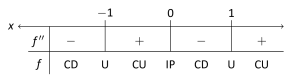

SolutionThe first thing we see is that itself is not defined at , having a domain of . Since the domain of is the union of three intervals, it makes sense that the concavity of could switch across intervals. We cannot say that has points of inflection at as they are not part of the domain, but we must still consider these -values to be important and will include them in our number line.

We need to find and . Using the Quotient Rule and simplifying, we find

To find the possible points of inflection, we seek to find where and where is not defined. Solving reduces to solving ; we find . We find that is not defined when , for then the denominator of is 0 (of course, is not defined at these points either).

The important -values at which concavity might switch are , and , which split the number line into four intervals as shown in our sign chart below. We determine the concavity on each. Keep in mind that all we are concerned with is the sign of on the interval.

- Interval 1,

-

: Select a number in this interval with a large magnitude (for instance, ). The denominator of will be positive. In the numerator, the will be positive and the term will be negative. Thus the numerator is negative and is negative. We conclude is concave down on .

- Interval 2,

-

: For any number in this interval, the term in the numerator will be negative, the term in the numerator will be positive, and the term in the denominator will be negative. Thus and is concave up on this interval.

- Interval 3,

-

: Any number in this interval will be positive and “small.” Thus the numerator is positive while the denominator is negative. Thus and is concave down on this interval.

- Interval 4,

-

: Choose a large value for . It is evident that , so we conclude that is concave up on .

We conclude that is concave up on and and concave down on and . There is only one point of inflection, , as is not defined at . Our work is confirmed by the graph of in Figure 3.4.4. Notice how is concave up whenever is positive, and concave down when is negative.

Recall that relative maxima and minima of are found at critical points of ; that is, they are found when or when is undefined. Likewise, the relative maxima and minima of are found when or when is undefined; note that these are the inflection points of .

What does a “relative maximum of ” mean? The derivative measures the rate of change of ; maximizing means finding where is increasing the most — where has the steepest tangent line. A similar statement can be made for minimizing ; it corresponds to where has the steepest negatively-sloped tangent line.

We utilize this concept in the next example.

Example 3.4.3 Understanding inflection points

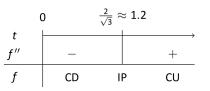

The sales of a certain product over a three-year span are modeled by , where is the time in years, shown in Figure 3.4.5. Over the first two years, sales are decreasing. Find the point at which sales are decreasing at their greatest rate.

SolutionWe want to maximize the rate of decrease, which is to say, we want to find where has a minimum. To do this, we find where is 0. We find and . Setting and solving, we get (we ignore the negative value of since it does not lie in the domain of our function ).

This is both the inflection point and the point of maximum decrease. This is the point at which things first start looking up for the company. After the inflection point, it will still take some time before sales start to increase, but at least sales are not decreasing quite as quickly as they had been.

A graph of and is given in Figure 3.4.6. When , sales are decreasing; note how at , is minimized. That is, sales are decreasing at the fastest rate at . On the interval of , is decreasing but concave up, so the decline in sales is “leveling off.”

Not every critical point corresponds to a relative extrema; has a critical point at but no relative maximum or minimum. Likewise, just because we cannot conclude concavity changes at that point. We were careful before to use terminology “possible point of inflection” since we needed to check to see if the concavity changed. The canonical example of without concavity changing is . At , but is always concave up, as shown in Figure 3.4.7.

The Second Derivative Test

The first derivative of a function gave us a test to find if a critical value corresponded to a relative maximum, minimum, or neither. The second derivative gives us another way to test if a critical point is a local maximum or minimum. The following theorem officially states something that is intuitive: if a critical value occurs in a region where a function is concave up, then that critical value must correspond to a relative minimum of , etc. See Figure 3.4.8 for a visualization of this.

Theorem 3.4.3 The Second Derivative Test

Let be a critical point of where is defined.

-

(a)

If , then has a local minimum at .

-

(b)

If , then has a local maximum at .

Note that if , then the Second Derivative Test is inconclusive. The Second Derivative Test relates to the First Derivative Test in the following way. If , then the graph is concave up at a critical point and itself is growing. Since and is growing at , then it must go from negative to positive at . This means the function goes from decreasing to increasing, indicating a local minimum at .

Example 3.4.4 Using the Second Derivative Test

Let . Find the critical points of and use the Second Derivative Test to label them as relative maxima or minima.

Solution††margin: Figure 3.4.9: A graph of in Example 3.4.4. The second derivative is evaluated at each critical point. When the graph is concave up, the critical point represents a local minimum; when the graph is concave down, the critical point represents a local maximum. Λ We find and We set and solve for to find the critical points (note that is not defined at , but neither is so this is not a critical point.) We find the critical points are . Evaluating at gives , so there is a local minimum at . Evaluating , determining a relative maximum at . These results are confirmed in Figure 3.4.9.

We have been learning how the first and second derivatives of a function relate information about the graph of that function. We have found intervals of increasing and decreasing, intervals where the graph is concave up and down, along with the locations of relative extrema and inflection points. In Chapter 1 we saw how limits explained asymptotic behavior. In the next section we combine all of this information to produce accurate sketches of functions.

Exercises 3.4

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

Sketch a graph of a function that is concave up on and is concave down on .

-

2.

Sketch a graph of a function that is: (a) Increasing, concave up on , (b) increasing, concave down on , (c) decreasing, concave down on and (d) increasing, concave down on .

-

3.

Is it possible for a function to be increasing and concave down on with a horizontal asymptote of ? If so, give a sketch of such a function.

-

4.

Is it possible for a function to be increasing and concave up on with a horizontal asymptote of ? If so, give a sketch of such a function.

Problems

-

5.

Given the graph of , identify the concavity of and its inflection points.

-

6.

Given the graph of , identify the concavity of and its inflection points.

In Exercises 7–16., a function is given.

-

(a)

Compute .

-

(b)

Graph and on the same axes (using technology is permitted) and verify Theorem 3.4.1.

-

7.

-

8.

-

9.

-

10.

-

11.

-

12.

-

13.

-

14.

-

15.

-

16.

In Exercises 17–36., a function is given.

-

(a)

Find the coordinates of the possible points of inflection of .

-

(b)

Create a number line to determine the intervals on which is concave up or concave down.

-

(c)

Find the critical points of and use the Second Derivative Test, when possible, to determine the relative extrema.

-

(d)

Find the values where has a relative maximum or minimum.

-

17.

-

18.

-

19.

-

20.

-

21.

-

22.

-

23.

-

24.

on

-

25.

-

26.

-

27.

on

-

28.

-

29.

-

30.

-

31.

-

32.

on

-

33.

-

34.

-

35.

-

36.