10.5 Calculus and Polar Functions

The previous section defined polar coordinates, leading to polar functions. We investigated plotting these functions and solving a fundamental question about their graphs, namely, where do two polar graphs intersect?

We now turn our attention to answering other questions, whose solutions require the use of calculus. A basis for much of what is done in this section is the ability to turn a polar function into a set of parametric equations. Using the identities and , we can create the parametric equations , and apply the concepts of Section 10.3.

Polar Functions and

We are interested in the lines tangent to a given graph, regardless of whether that graph is produced by rectangular, parametric, or polar equations. In each of these contexts, the slope of the tangent line is . Given , we are generally not concerned with ; that describes how fast changes with respect to . Instead, we will use , to compute .

Using Key Idea 10.3.1 we have

Each of the two derivatives on the right hand side of the equality requires the use of the Product Rule. We state the important result as a Key Idea.

Key Idea 10.5.1 Finding with Polar Functions

Let be a polar function. With and ,

Example 10.5.1 Finding with polar functions.

Consider the limaçon on .

-

1.

Find the rectangular equations of the tangent and normal lines to the graph at .

-

2.

Find where the graph has vertical and horizontal tangent lines.

Solution

-

1.

We start by computing . With , we have

When , (this requires a bit of simplification). In rectangular coordinates, the point on the graph at is . Thus the rectangular equation of the line tangent to the limaçon at is

The limaçon and the tangent line are graphed in Figure 10.5.1.

The normal line has the opposite-reciprocal slope as the tangent line, so its equation is

-

2.

To find the horizontal lines of tangency, we find where (when the denominator does not equal 0); thus we find where the numerator of our equation for is 0.

On , when .

Setting gives . We want the results in ; we also recognize there are two solutions, one in the 3 quadrant and one in the 4. Using reference angles, we have our two solutions as and radians. The four points we obtained where the limaçon has a horizontal tangent line are given in Figure 10.5.1 with black-filled dots.

To find the vertical lines of tangency, we determine where is undefined by setting the denominator of (when the numerator does not equal 0).

††margin: Figure 10.5.1: The limaçon in Example 10.5.1 with its tangent line at and points of vertical and horizontal tangency.Convert the term to : Recognize this as a quadratic in the variable . Using the quadratic formula, we have We solve and :

In each of the solutions above, we only get one of the possible two solutions as only returns solutions in , the 4 and quadrants. Again using reference angles, we have:

and

These points are also shown in Figure 10.5.1 with white-filled dots.

When the graph of the polar function intersects the pole, it means that for some angle . Making this substitution in the formula for given in Key Idea 10.5.1 we see

This equation makes an interesting point. It tells us the slope of the tangent line at the pole is ; some of our previous work (see, for instance, Example 10.4.3) shows us that the line through the pole with slope has polar equation . Thus when a polar graph touches the pole at , the equation of the tangent line at the pole is .

Example 10.5.2 Finding tangent lines at the pole

Let , a limaçon. Find the equations of the lines tangent to the graph at the pole. ††margin: Figure 10.5.2: Graphing the tangent lines at the pole in Example 10.5.2.

SolutionWe need to know when .

Thus the equations of the tangent lines, in polar, are and . In rectangular form, the tangent lines are and . The full limaçon can be seen in Figure 10.5.1; we zoom in on the tangent lines in Figure 10.5.2.

Area

When using rectangular coordinates, the equations and defined vertical and horizontal lines, respectively, and combinations of these lines create rectangles (hence the name “rectangular coordinates”). It is then somewhat natural to use rectangles to approximate area as we did when learning about the definite integral.

When using polar coordinates, the equations and form lines through the origin and circles centered at the origin, respectively, and combinations of these curves form sectors of circles. It is then somewhat natural to calculate the area of regions defined by polar functions by first approximating with sectors of circles.

Consider Figure 10.5.3 (a) where a region defined by on is given. (Note how the “sides” of the region are the lines and , whereas in rectangular coordinates the “sides” of regions were often the vertical lines and .)

Partition the interval into equally spaced subintervals as . The radian length of each subinterval is , representing a small change in angle. The area of the region defined by the subinterval can be approximated with a sector of a circle with radius , for some in . The area of this sector is . This is shown in part (b) of the figure, where has been divided into 4 subintervals. We approximate the area of the whole region by summing the areas of all sectors: ††margin: (a) (b) Figure 10.5.3: Computing the area of a polar region.

This is a Riemann sum. By taking the limit of the sum as , we find the exact area of the region in the form of a definite integral.

Theorem 10.5.1 Area of a Polar Region

Let be continuous and non-negative on , where . The area of the region bounded by the curve and the lines and is

The theorem states that . This ensures that region does not overlap itself, which would give a result that does not correspond directly to the area.

Example 10.5.3 Area of a polar region

Find the area of the circle defined by . (Recall this circle has radius .)

SolutionThis is a direct application of Theorem 10.5.1. The circle is traced out on , leading to the integral ††margin: Note: Example 10.5.3 requires the use of the integral . This is handled well by using the half angle formula as found in the back of this text. Due to the nature of the area formula, integrating and is required often. We offer here these indefinite integrals as a time-saving measure.

| Area | |||

Of course, we already knew the area of a circle with radius . We did this example to demonstrate that the area formula is correct.

Example 10.5.4 Area of a polar region

Find the area of the cardioid bound between and , as shown in Figure 10.5.4.

SolutionThis is again a direct application of Theorem 10.5.1. ††margin: Figure 10.5.4: Finding the area of the shaded region of a cardioid in Example 10.5.4.

| Area | |||

Area Between Curves

Our study of area in the context of rectangular functions led naturally to finding area bounded between curves. We consider the same in the context of polar functions.

Consider the shaded region shown in Figure 10.5.5. We can find the area of this region by computing the area bounded by and subtracting the area bounded by on . Thus

Key Idea 10.5.2 Area Between Polar Curves

The area of the region bounded by and , and , where on , is

Example 10.5.5 Area between polar curves

Find the area bounded between the curves and , as shown in Figure 10.5.6.

SolutionWe need to find the points of intersection between these two functions. Setting them equal to each other, we find:

Thus we integrate on .

| Area | |||

Amazingly enough, the area between these curves has a “nice” value.

Example 10.5.6 Area defined by polar curves

Find the area bounded between the polar curves and , as shown in Figure 10.5.7 (a).

SolutionWe need to find the point of intersection between the two curves. Setting the two functions equal to each other, we have

In part (b) of the figure, we zoom in on the region and note that it is not really bounded between two polar curves, but rather by two polar curves, along with . The dashed line breaks the region into its component parts. Below the dashed line, the region is defined by , and . (Note: the dashed line lies on the line .) Above the dashed line the region is bounded by and . Since we have two separate regions, we find the area using two separate integrals.

Call the area below the dashed line and the area above the dashed line . They are determined by the following integrals:

(The upper bound of the integral computing is as is at the pole when .)

We omit the integration details and let the reader verify that and ; the total area is .

Arc Length

As we have already considered the arc length of curves defined by rectangular and parametric equations, we now consider it in the context of polar equations. Recall that the arc length of the graph defined by the parametric equations , on is

| (10.1) |

Now consider the polar function . We again use the identities and to create parametric equations based on the polar function. We compute and as done before when computing , then apply Equation (10.1).

The expression can be simplified a great deal; we leave this as an exercise and state that

This leads us to the arc length formula.

Key Idea 10.5.3 Arc Length of Polar Curves

Let be a polar function with continuous on an open interval containing , on which the graph traces itself only once. The arc length of the graph on is

Example 10.5.7 Arc Length of Polar Curves

Find the arc length of the cardioid .

SolutionWith , we have . The cardioid is traced out once on , giving us our bounds of integration. Applying Key Idea 10.5.3 we have

Since the on and on we separate the integral into two parts

Using the symmetry of the cardioid and -substitution () we simplify the integration to

Example 10.5.8 Arc length of a limaçon

Find the arc length of the limaçon .

SolutionWith , we have . The limaçon is traced out once on , giving us our bounds of integration. Applying Key Idea 10.5.3, we have

The final integral cannot be solved in terms of elementary functions, so we resorted to a numerical approximation. (Simpson’s Rule, with , approximates the value with . Using gives the value above, which is accurate to 4 places after the decimal.)

Surface Area

The formula for arc length leads us to a formula for surface area. The following Key Idea is based on Key Idea 10.3.4.

Key Idea 10.5.4 Surface Area of a Solid of Revolution

Consider the graph of the polar equation , where is continuous on an open interval containing on which the graph does not cross itself.

-

1.

The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph about the initial ray () is:

-

2.

The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph about the line is:

Example 10.5.9 Surface area determined by a polar curve

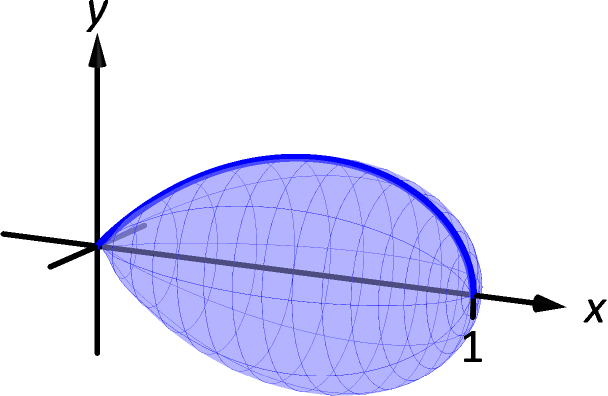

Find the surface area formed by revolving one petal of the rose curve about its central axis (see Figure 10.5.9).

Solution††margin:

(a) (b)

Figure 10.5.9: Finding the surface area of a rose-curve petal that is revolved around its central axis.

We choose, as implied by the figure, to revolve the portion of the curve that lies on about the initial ray. Using Key Idea 10.5.4 and the fact that , we have

(b)

Figure 10.5.9: Finding the surface area of a rose-curve petal that is revolved around its central axis.

We choose, as implied by the figure, to revolve the portion of the curve that lies on about the initial ray. Using Key Idea 10.5.4 and the fact that , we have

| Surface Area | |||

The integral is another that cannot be evaluated in terms of elementary functions. Simpson’s Rule, with , approximates the value at .

This chapter has been about curves in the plane. While there is great mathematics to be discovered in the two dimensions of a plane, we live in a three dimensional world and hence we should also look to do mathematics in 3D — that is, in space. The next chapter begins our exploration into space by introducing the topic of vectors, which are incredibly useful and powerful mathematical objects.

Exercises 10.5

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

Given polar equation , how can one create parametric equations of the same curve?

-

2.

With rectangular coordinates, it is natural to approximate area with ; with polar coordinates, it is natural to approximate area with .

Problems

In Exercises 3–10, find:

-

(a)

-

(b)

the equation of the tangent and normal lines to the curve at the indicated -value.

-

3.

;

-

4.

;

-

5.

;

-

6.

;

-

7.

;

-

8.

;

-

9.

;

-

10.

;

In Exercises 11–14, find the values of in the given interval where the graph of the polar function has horizontal and vertical tangent lines.

-

11.

;

-

12.

;

-

13.

;

-

14.

;

In Exercises 15–18, find the equation of the lines tangent to the graph at the pole.

-

15.

;

-

16.

;

-

17.

;

-

18.

;

In Exercises 19–30, find the area of the described region.

-

19.

Enclosed by the circle: ,

-

20.

Enclosed by the circle

-

21.

Enclosed by one petal of

-

22.

Enclosed by one petal of the rose curve , where is a positive integer.

-

23.

Enclosed by the cardioid

-

24.

Enclosed by the inner loop of the limaçon

-

25.

Enclosed by the outer loop of the limaçon (including area enclosed by the inner loop)

-

26.

Enclosed between the inner and outer loop of the limaçon

-

27.

Enclosed by and , as shown:

-

28.

Enclosed by and , as shown:

-

29.

Enclosed by and , as shown:

-

30.

Enclosed by and , as shown:

In Exercises 31–36, answer the questions involving arc length.

-

31.

Let and . Show, as suggested by the text, that

-

32.

Use the arc length formula to compute the arc length of the circle .

-

33.

Use the arc length formula to compute the arc length of the circle .

-

34.

Use the arc length formula to compute the arc length of .

-

35.

Approximate the arc length of one petal of the rose curve with Simpson’s Rule and

-

36.

Approximate the arc length of the cardioid with Simpson’s Rule and

In Exercises 37–42, answer the questions involving surface area.

-

37.

Use Key Idea 10.5.4 to find the surface area of the sphere formed by revolving the circle about the initial ray.

-

38.

Use Key Idea 10.5.4 to find the surface area of the sphere formed by revolving the circle about the initial ray.

-

39.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving the cardioid about the initial ray.

-

40.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving the circle about the line .

-

41.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving the line , , about the line .

-

42.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving the line , , about the initial ray.