13.8 Extreme Values

Given a function , we are often interested in points where takes on the largest or smallest values. For instance, if represents a cost function, we would likely want to know what values minimize the cost. If represents the ratio of a volume to surface area, we would likely want to know where is greatest. This leads to the following definition.

Definition 13.8.1 Relative and Absolute Extrema

Let be defined on a set containing the point .

-

1.

If there is an open disk containing such that for all in and , then has a relative maximum at ; if for all in and , then has a relative minimum at .

-

2.

If for all in , then has an absolute maximum at ; if for all in , then has an absolute minimum at .

-

3.

If has a relative maximum or minimum at , then has a relative extrema at ; if has an absolute maximum or minimum at , then has an absolute extrema at .

If has a relative or absolute maximum at , it means every curve on the surface of through will also have a relative or absolute maximum at . Recalling what we learned in Section 3.1, the slopes of the tangent lines to these curves at must be 0 or undefined. Since directional derivatives are computed using and , we are led to the following definition and theorem.

Definition 13.8.2 Critical Point

Let be continuous on an open set . A critical point of is a point in such that

-

•

and , or

-

•

or is undefined.

Theorem 13.8.1 Critical Points and Relative Extrema

Let be defined on an open set containing . If has a relative extrema at , then is a critical point of .

Therefore, to find relative extrema, we find the critical points of and determine which correspond to relative maxima, relative minima, or neither.

Watch the video:

Local Maximum and Minimum Values / Function of Two Variables from https://youtu.be/Hm5QnuDjNmY

The following examples demonstrate this process.

Example 13.8.1 Finding critical points and relative extrema

Let . Find the relative extrema of .

SolutionWe start by computing the partial derivatives of :

Each is never undefined. A critical point occurs when and are simultaneously 0, leading us to solve the following system of linear equations:

This solution to this system is , . (Check that at , both and are 0.)

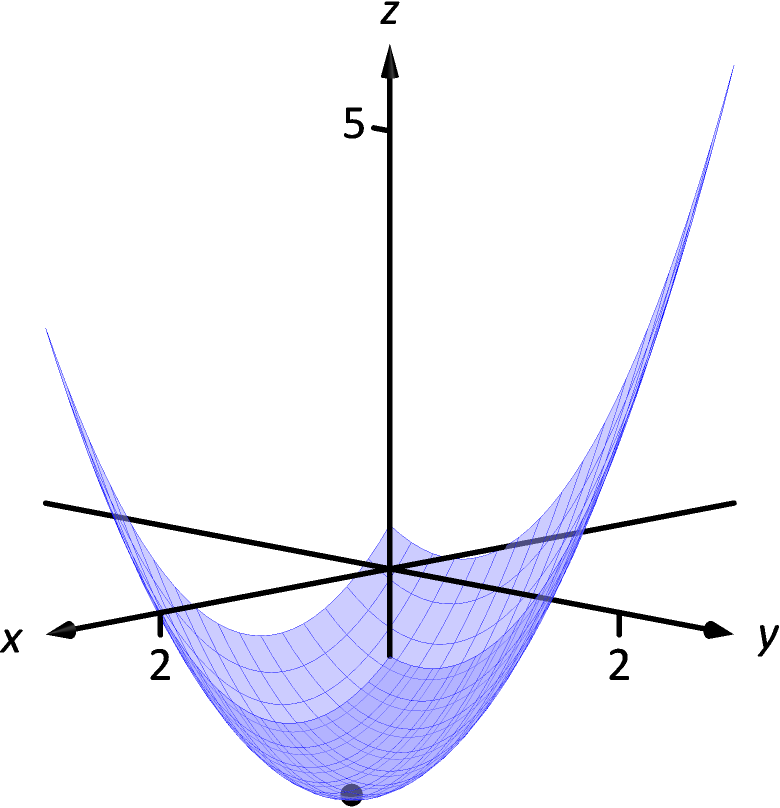

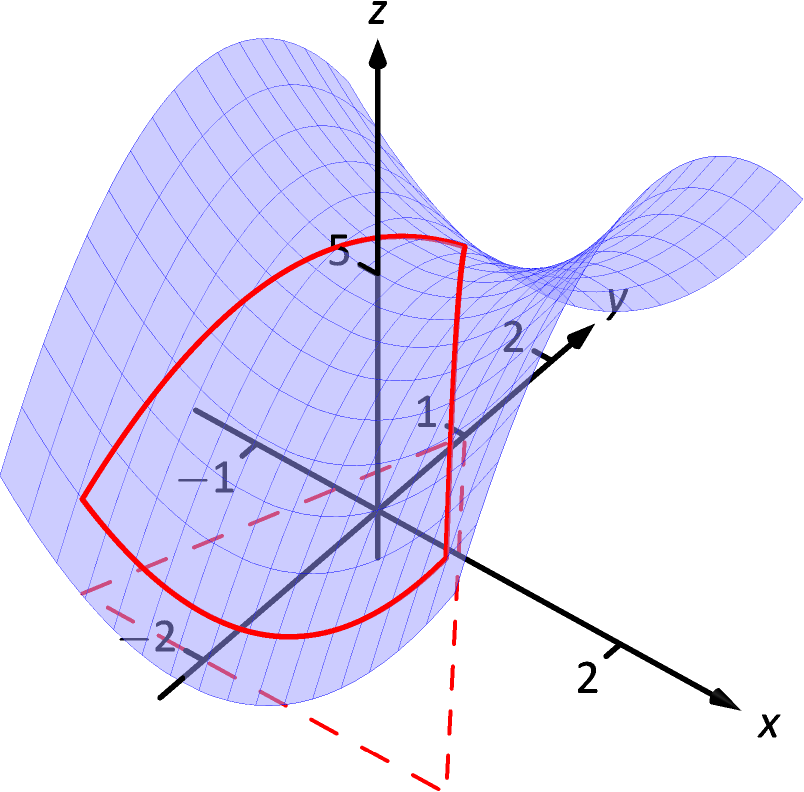

††margin:

Figure 13.8.1: The surface in Example 13.8.1 with its absolute minimum indicated.

Figure 13.8.1: The surface in Example 13.8.1 with its absolute minimum indicated.

The graph in Figure 13.8.1 shows along with this critical point. It is clear from the graph that this is a relative minimum; further consideration of the function shows that this is actually the absolute minimum.

Example 13.8.2 Finding critical points and relative extrema

Let . Find the relative extrema of .

SolutionWe start by computing the partial derivatives of :

It is clear that when & , and that when & . At , both and are not , but rather undefined. The point is still a critical point, though, because the partial derivatives are undefined. This is the only critical point of .

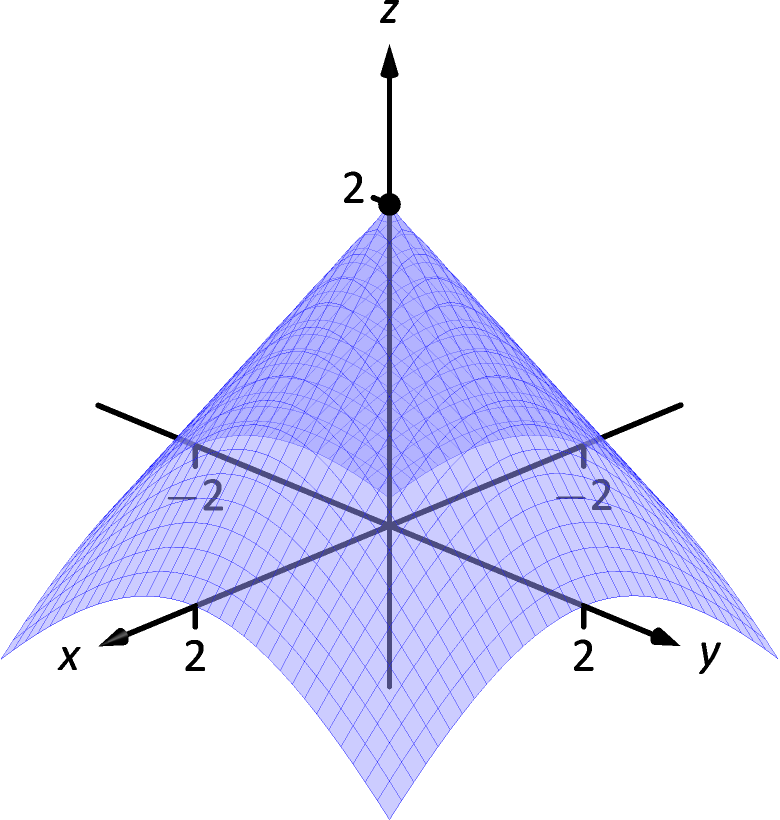

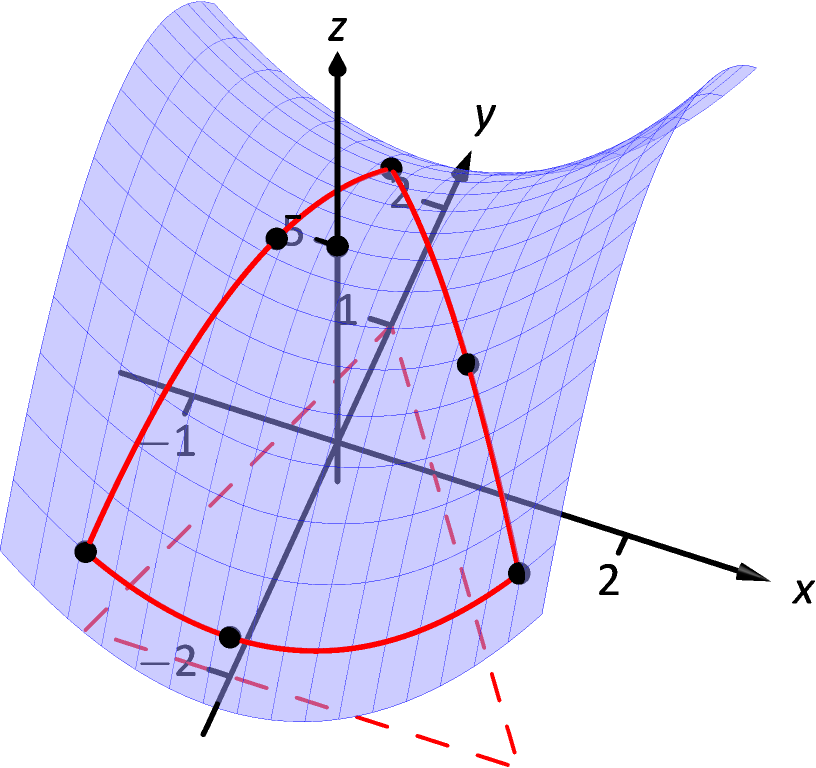

††margin:

Figure 13.8.2: The surface in Example 13.8.2 with its absolute maximum indicated.

Figure 13.8.2: The surface in Example 13.8.2 with its absolute maximum indicated.

The surface of is graphed in Figure 13.8.2 along with the point . The graph shows that this point is the absolute maximum of .

In each of the previous two examples, we found a critical point of and then determined whether or not it was a relative (or absolute) maximum or minimum by graphing. It would be nice to be able to determine whether a critical point corresponded to a max or a min without a graph. Before we develop such a test, we do one more example that sheds more light on the issues our test needs to consider.

Example 13.8.3 Finding critical points and relative extrema

Let . Find the relative extrema of .

SolutionOnce again we start by finding the partial derivatives of :

Each is always defined. Setting each equal to 0 and solving for and , we find

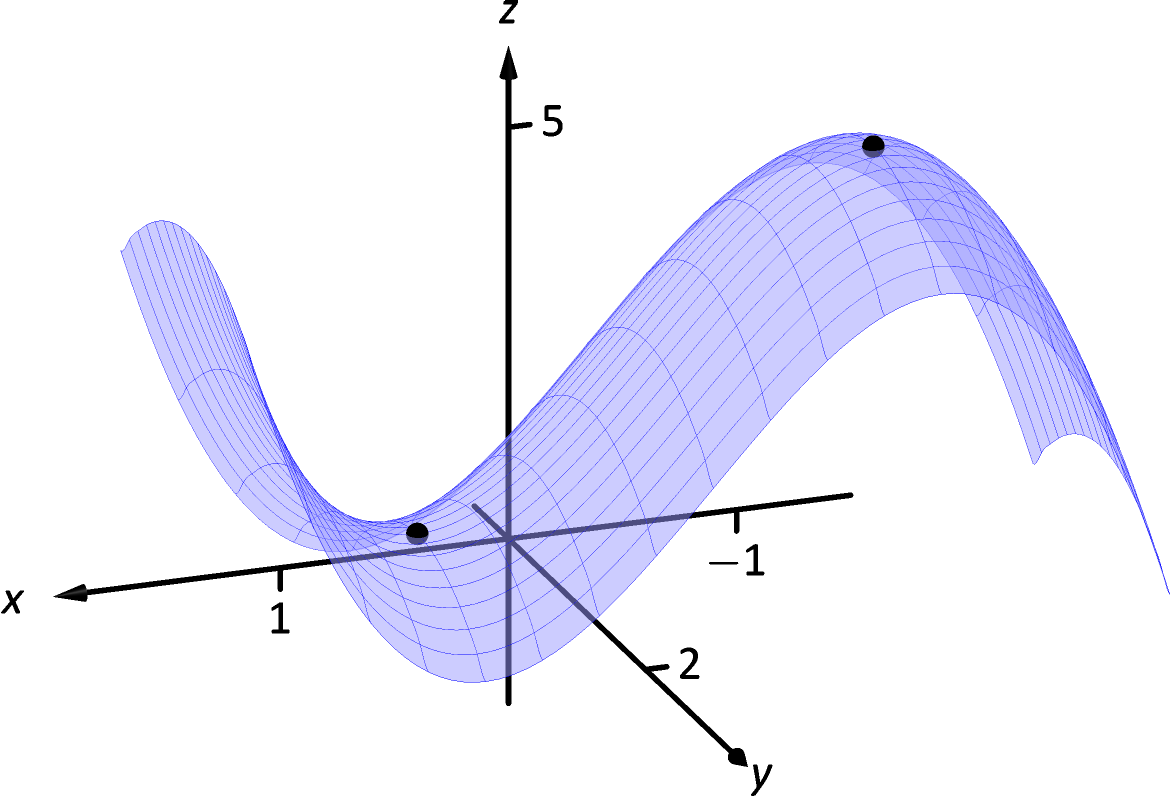

We have two critical points: and . To determine if they correspond to a relative maximum or minimum, we consider the graph of in Figure 13.8.3.

††margin:

Figure 13.8.3: The surface in Example 13.8.3 with both critical points marked.

Figure 13.8.3: The surface in Example 13.8.3 with both critical points marked.

The critical point clearly corresponds to a relative maximum. However, the critical point at is neither a maximum nor a minimum, displaying a different, interesting characteristic.

If one walks parallel to the -axis towards this critical point, then this point becomes a relative maximum along this path. But if one walks towards this point parallel to the -axis, this point becomes a relative minimum along this path. A point that seems to act as both a max and a min is a saddle point. A formal definition follows.

Definition 13.8.3 Saddle Point

Let be in the domain of where and at . We say is a saddle point of if, for every open disk containing , there are points and in such that and .

At a saddle point, the instantaneous rate of change in all directions is 0 and there are points nearby with -values both less than and greater than the -value of the saddle point.

Before Example 13.8.3 we mentioned the need for a test to differentiate between relative maxima and minima. We now recognize that our test also needs to account for saddle points. To do so, we consider the second partial derivatives of .

Recall that with single variable functions, such as , if , then is concave up at , and if , then has a relative minimum at . (We called this the Second Derivative Test.) Note that at a saddle point, it seems the graph is “both” concave up and concave down, depending on which direction you are considering.

It would be nice if the following were true:

| and | relative minimum | |

| and | relative maximum | |

| and have opposite signs | saddle point. |

However, this is not the case. Functions exist where and are both positive but a saddle point still exists. In such a case, while the concavity in the -direction is up (i.e., ) and the concavity in the -direction is also up (i.e., ), the concavity switches somewhere in between the - and -directions.

To account for this, consider . Since and are equal when continuous (refer back to Theorem 13.3.1), we can rewrite this as . Then can be used to test whether the concavity at a point changes depending on direction. If , the concavity does not switch (i.e., at that point, the graph is concave up or down in all directions). If , the concavity does switch. If , our test fails to determine whether concavity switches or not. We state the use of in the following theorem.

Theorem 13.8.2 Second Derivative Test

Let be defined on an open set containing a critical point where all second order derivatives of are continuous at . Define

-

1.

If and , then is a relative minimum of .

-

2.

If and , then is a relative maximum of .

-

3.

If , then is a saddle point of .

-

4.

If , the test is inconclusive.

-

Proof

Let be a unit vector. Then at the critical point , . This means that along the line , is a critical point that is a maximum or minimum according to the sign of . Now,because and are continuous and therefore equal.

Suppose now that . Then we must have , and we can complete the square to see that

Because we assumed , everything in the brackets is positive, and always has the same sign as . This shows parts 1 and 2.

If , our task is easier because we only need to find two different that give opposite signs. If , let and we can choose

Similarly, if , let and we can choose

Finally, if , then has opposite signs for the vectors and . ∎

We first practice using this test with the function in the previous example, where we visually determined we had a relative maximum and a saddle point.

Example 13.8.4 Using the Second Derivative Test

Let as in Example 13.8.3. Determine whether the function has a relative minimum, maximum, or saddle point at each critical point.

SolutionWe determined previously that the critical points of are and . To use the Second Derivative Test, we must find the second partial derivatives of :

Thus .

At : , and . By the Second Derivative Test, has a relative maximum at .

At : . The Second Derivative Test states that has a saddle point at .

The Second Derivative Test confirmed what we determined visually.

Example 13.8.5 Using the Second Derivative Test

Find the relative extrema of .

SolutionWe start by finding the first and second partial derivatives of :

We find the critical points by finding where and are simultaneously 0 (they are both never undefined). Setting , we have:

This implies that for , either or .

Assume then consider :

Thus if , we have either or , giving two critical points: and .

Going back to , now assume , i.e., that , then consider :

Thus if , giving the critical point .

With , we apply the Second Derivative Test to each critical point.

At , , so is a saddle point.

At , , so is also a saddle point.

At , and , so is a relative minimum.

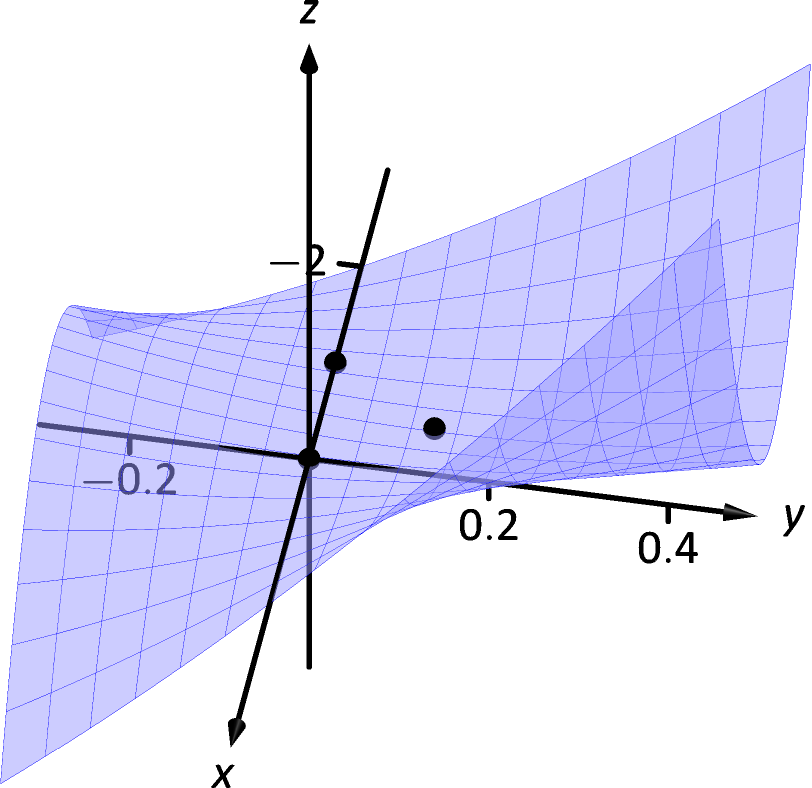

††margin:

Figure 13.8.4: Graphing from Example 13.8.5 and its relative extrema.

Figure 13.8.4: Graphing from Example 13.8.5 and its relative extrema.

Figure 13.8.4 shows a graph of and the three critical points. Note how this function does not vary much near the critical points — that is, visually it is difficult to determine whether a point is a saddle point or relative minimum (or even a critical point at all!). This is one reason why the Second Derivative Test is so important to have.

Constrained Optimization

When optimizing functions of one variable such as , we made use of Theorem 3.1.1, the Extreme Value Theorem, that said that over a closed interval , a continuous function has both a maximum and minimum value. To find these maximum and minimum values, we evaluated at all critical points in the interval, as well as at the endpoints (the “boundary”) of the interval.

A similar theorem and procedure applies to functions of two variables. A continuous function over a closed set also attains a maximum and minimum value (see the following theorem). We can find these values by evaluating the function at the critical points in the set and over the boundary of the set. After formally stating this extreme value theorem, we give examples.

Theorem 13.8.3 Extreme Value Theorem

Let be a continuous function on a closed, bounded set . Then has an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum value on .

Example 13.8.6 Finding extrema on a closed set

Let and let be the triangle with vertices , and . Find the maximum and minimum values of on .

SolutionIt can help to see a graph of along with the set . In Figure 13.8.5(a) the triangle defining is shown in the - plane in a dashed line. Above it is the surface of ; we are only concerned with the portion of enclosed by the “triangle” on its surface.

(a)

(b)

Figure 13.8.5: Plotting the surface of along with the restricted domain .

(a)

(b)

Figure 13.8.5: Plotting the surface of along with the restricted domain .

We begin by finding the critical points of . With and , we find only one critical point, at .

We now find the maximum and minimum values that attains along the boundary of , that is, along the edges of the triangle. In Figure 13.8.5(b) we see the triangle sketched in the plane with the equations of the lines forming its edges labeled.

Start with the bottom edge, along the line . If is , then on the surface, we are considering points ; that is, our function reduces to . We want to maximize/minimize on the interval . To do so, we evaluate at its critical points and at the endpoints. The critical points of are found by setting its derivative equal to 0:

so that we will need to evaluate at the points , , and .

We need to do this process twice more, for the other two edges of the triangle.

Along the left edge, along the line , we substitute in for in :

We want the maximum and minimum values of on the interval , so we evaluate at its critical points and the endpoints of the interval. We find the critical points:

so that we will need to evaluate at the points , , and .

Finally, we evaluate along the right edge of the triangle, where .

The critical points of are:

so that we will need to evaluate at the points , , and .

Figure 13.8.6: The surface of along with important points along the boundary of and the interior.

Figure 13.8.6: The surface of along with important points along the boundary of and the interior.

We now evaluate at a total of 7 different places, all shown in Figure 13.8.6.

Of all the -values found, the maximum is , found at ; the minimum is 1, found at .

This portion of the text is entitled “Constrained Optimization” because we want to optimize a function (i.e., find its maximum and/or minimum values) subject to a constraint — some limit to what values the function can attain. In the previous example, we constrained ourselves by considering a function only within the boundary of a triangle. This was largely arbitrary; the function and the boundary were chosen just as an example, with no real “meaning” behind the function or the chosen constraint.

However, solving constrained optimization problems is a very important topic in applied mathematics. The techniques developed here are the basis for solving larger problems, where more than two variables are involved.

We illustrate the technique once more with a classic problem.

Example 13.8.7 Constrained Optimization

The U.S. Postal Service states that the girth+length of Standard Post Package must not exceed 130”. Given a rectangular box, the “length” is the longest side, and the “girth” is twice the width+height.

Given a rectangular box where the width and height are equal, what are the dimensions of the box that give the maximum volume subject to the constraint of the size of a Standard Post Package?

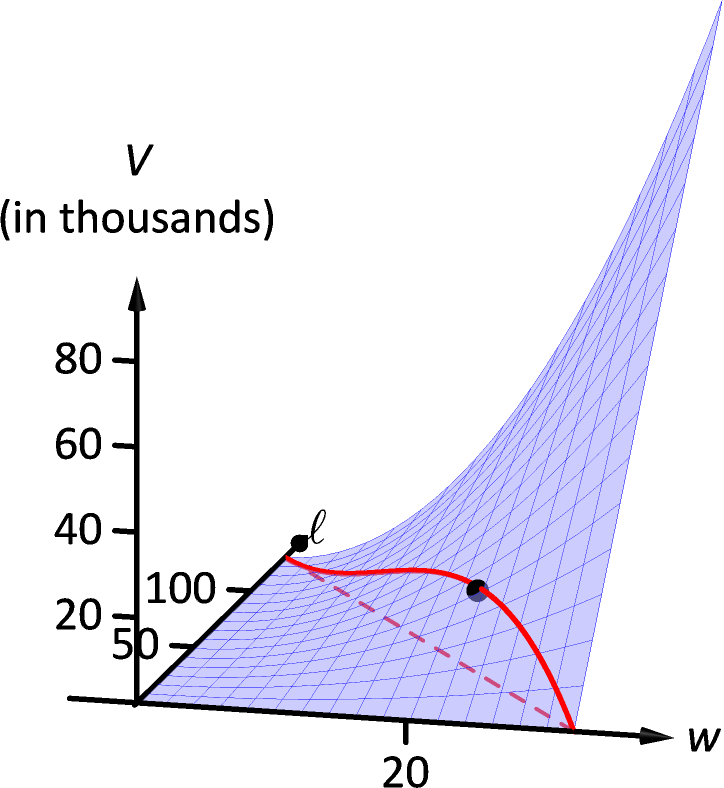

SolutionLet , , and denote the width, height, and length of a rectangular box; we assume here that . The girth is then . The volume of the box is . We wish to maximize this volume subject to the constraint , or . (Common sense also indicates that , so that we don’t need to check the boundary where either is zero.)

We begin by finding the critical points of . We find that and ; these are simultaneously 0 only when . These give a volume of 0, so we can ignore these critical points.

We now consider the volume along the constraint Along this line, we have:

The constraint is applicable on the -interval as indicated in the figure. Thus we want to maximize on .

Finding the critical points of , we take the derivative and set it equal to 0:

We found two critical points: when and when . We again ignore the solution; the maximum volume, subject to the constraint, comes at , This gives a volume of in3.

Figure 13.8.7: Graphing the volume of a box with girth and length , subject to a size constraint.

Figure 13.8.7: Graphing the volume of a box with girth and length , subject to a size constraint.

The volume function is shown in Figure 13.8.7 along with the constraint . As done previously, the constraint is drawn dashed in the - plane and also along the surface of the function. The point where the volume is maximized is indicated.

It is hard to overemphasize the importance of optimization. In “the real world,” we routinely seek to make something better. By expressing the something as a mathematical function, “making something better” means “optimize some function.”

The techniques shown here are only the beginning of an incredibly important field. Many functions that we seek to optimize are incredibly complex, making the step of “find the gradient and set it equal to ” highly nontrivial. Mastery of the principles here are key to being able to tackle these more complicated problems.

Exercises 13.8

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

T/F: Theorem 13.8.1 states that if has a critical point at , then has a relative extrema at .

-

2.

T/F: A point is a critical point of if and are both 0 at .

-

3.

T/F: A point is a critical point of if or are undefined at .

-

4.

Explain what it means to “solve a constrained optimization” problem.

Problems

In Exercises 5–18, find the critical points of the given function. Use the Second Derivative Test to determine if each critical point corresponds to a relative maximum, minimum, or saddle point.

-

5.

-

6.

-

7.

-

8.

-

9.

-

10.

-

11.

-

12.

-

13.

-

14.

-

15.

-

16.

-

17.

-

18.

In Exercises 19–24, find the absolute maximum and minimum of the function subject to the given constraint.

-

19.

, constrained to the triangle with vertices , and .

-

20.

, constrained to the region bounded by and .

-

21.

, constrained to the region bounded by the circle .

-

22.

, constrained to the region bounded by the parabola and the line .

-

23.

, constrained to the square with vertices , , , and .

-

24.

, constrained to the region bounded by the circle .

-

25.

Find the dimensions of the box without a top that has a volume of and the least possible surface area.

-

26.

Show that there are boxes without a top that have a volume of and arbitrarily large surface area.