10.3 Calculus and Parametric Equations

The previous section defined curves based on parametric equations. In this section we’ll employ the techniques of calculus to study these curves.

We are still interested in lines tangent to points on a curve. They describe how the -values are changing with respect to the -values, they are useful in making approximations, and they indicate instantaneous direction of travel.

The slope of the tangent line is still , and the Chain Rule allows us to calculate this in the context of parametric equations. If and , the Chain Rule states that

Solving for , we get

provided that . This is important so we label it a Key Idea.

Key Idea 10.3.1 Finding with Parametric Equations.

Let and , where and are differentiable on some open interval and on . Then

We use this to define the tangent line.

Definition 10.3.1 Tangent Lines

Let a curve be parameterized by and , where and are differentiable functions on some interval containing . The tangent line to at is the line

Notice that the tangent line goes through the point . It is possible for parametric curves to have horizontal and vertical tangents. As expected a horizontal tangent occurs whenever or when (provided ). Similarly, a vertical tangent occurs whenever is undefined or when (provided ). When is defined, however, the tangent line has slope .

Definition 10.3.2 Normal Lines

The normal line to a curve at a point is the line through and perpendicular to the tangent line at . For the normal line is the line through with slope , provided .

As with the tangent line we note that it is possible for a normal line to be vertical or horizontal. A horizontal normal line occurs whenever is undefined or when (provided ). Similarly, a vertical normal line occurs whenever or when (provided ). In other words, if the curve has a vertical tangent at the normal line will be horizontal and if the tangent is horizontal the normal line will be a vertical line.

Example 10.3.1 Tangent and Normal Lines to Curves

Let and , and let be the curve defined by these equations.

-

(a)

Find the equations of the tangent and normal lines to at .

-

(b)

Find where has vertical and horizontal tangent lines.

Solution

-

(a)

We start by computing and . Thus

Make note of something that might seem unusual: is a function of , not . Just as points on the curve are found in terms of , so are the slopes of the tangent lines.

††margin: Figure 10.3.1: Graphing tangent and normal lines in Example 10.3.1. ΛThe point on at is . The slope of the tangent line is and the slope of the normal line is . Thus,

-

•

the equation of the tangent line is , and

-

•

the equation of the normal line is .

This is illustrated in Figure 10.3.1.

-

•

-

(b)

To find where has a horizontal tangent line, we set and solve for . In this case, this amounts to setting and solving for (and making sure that ).

The point on corresponding to is ; the tangent line at that point is horizontal (hence with equation ). To find where has a vertical tangent line, we find where it has a horizontal normal line, and set . This amounts to setting and solving for (and making sure that ).

The point on corresponding to is . The tangent line at that point is . The points where the tangent lines are vertical and horizontal are indicated on the graph in Figure 10.3.1.

Example 10.3.2 Tangent and Normal Lines to a Circle

(a)

Find where the unit circle, defined by and on , has vertical and horizontal tangent lines.

(b)

Find the equation of the normal line at .

Solution

-

(a)

We compute the derivative following Key Idea 10.3.1:

The derivative is when ; that is, when . These are the points and on the circle.

The normal line is horizontal (and hence, the tangent line is vertical) when ; that is, when , corresponding to the points and on the circle. These results should make intuitive sense.

-

(b)

The slope of the normal line at is . This normal line goes through the point , giving the line ††margin: Figure 10.3.2: Illustrating how a circle’s normal lines pass through its center. Λ

as long as . It is an important fact to recognize that the normal lines to a circle pass through its center, as illustrated in Figure 10.3.2. Stated in another way, any line that passes through the center of a circle intersects the circle at right angles.

Example 10.3.3 Tangent lines when is not defined

Find the equation of the tangent line to the astroid , at , shown in Figure 10.3.3.

SolutionWe start by finding and : ††margin: Figure 10.3.3: A graph of an astroid. Λ

Note that both of these are 0 at ; the curve is not smooth at forming a cusp on the graph. Evaluating at this point returns the indeterminate form of “0/0”.

We can, however, examine the slopes of tangent lines near , and take the limit as .

We have accomplished something significant. When the derivative returns an indeterminate form at , we can define its value by setting it to be , if that limit exists. This allows us to find slopes of tangent lines at cusps, which can be very beneficial.

We found the slope of the tangent line at to be 0; therefore the tangent line is , the -axis.

Concavity

We continue to analyze curves in the plane by considering their concavity; that is, we are interested in , “the second derivative of with respect to .” To find this, we need to find the derivative of with respect to ; that is,

but recall that is a function of , not , making this computation not straightforward.

To make the upcoming notation a bit simpler, let . We want ; that is, we want . We again appeal to the Chain Rule. Note:

In words, to find , we first take the derivative of with respect to , then divide by . We restate this as a Key Idea.

Key Idea 10.3.2 Finding with Parametric Equations

Let and be twice differentiable functions on an open interval , where on . Then

Examples will help us understand this Key Idea.

Example 10.3.4 Concavity of Plane Curves

Let and as in Example 10.3.1. Determine the -intervals on which the graph is concave up/down.

SolutionConcavity is determined by the second derivative of with respect to , , so we compute that here following Key Idea 10.3.2.

In Example 10.3.1, we found and . So:

The graph of the parametric functions is concave up when and concave down when . We determine the intervals when the second derivative is greater/less than 0 by first finding when it is 0 or undefined.

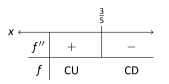

As the numerator of is never 0, for all . It is undefined when ; that is, when . Following the work established in Section 3.4, we look at values of greater or less than on a number line:

Reviewing Example 10.3.1, we see that when , the graph of the parametric equations has a vertical tangent line. This point is also a point of inflection for the graph, illustrated in Figure 10.3.4.

Example 10.3.5 Concavity of Plane Curves

Find the points of inflection of the graph of the parametric equations , , for .

SolutionWe need to compute and .

The possible points of inflection are found by setting . This is not trivial, as equations that mix polynomials and trigonometric functions generally do not have “nice” solutions.

In Figure 10.3.5(a) we see a plot of the second derivative. It shows that it has zeros at approximately and . These approximations are not very good, made only by looking at the graph. Newton’s Method provides more accurate approximations. Accurate to 2 decimal places, we have:

The corresponding points have been plotted on the graph of the parametric equations in Figure 10.3.5(b). Note how most occur near the -axis, but not exactly on the axis.

Area with Parametric Equations

We will now find a formula for determining the area under a parametric curve given by the parametric equations

We will also need to further add in the assumption that the curve is traced out exactly once as t increases from to . First, recall how to find the area under on :

Now think of the parametric equation as a substitution in the integral, assuming that and for the purposes of this formula. (There is actually no reason to assume that this will always be the case and so we’ll give a corresponding formula later if it’s the opposite case ( and ).)

In order to substitute, we’ll need . Plugging this into the area formula above and making sure to change the limits to their corresponding values gives us

Since we don’t know what is, we’ll use the fact that

and arrive at the formula that we want.

Key Idea 10.3.3 Area Under a Parametric Curve

The area under the parametric curve given by , , for is

On the other hand, if we should happen to have and , then the formula would be

Let’s work an example.

Example 10.3.6 Finding the area under a parametric curve

Determine the area under the cycloid given by the parametric equations

SolutionFirst, notice that we’ve switched the parameter to for this problem. This is to make sure that we don’t get too locked into always having as the parameter.

Now, we could graph this to verify that the curve is traced out exactly once for the given range if we wanted to.

There really isn’t too much to this example other than plugging the parametric equations into the formula. We’ll first need the derivative of the parametric equation for however.

The area is then

Arc Length

We continue our study of the features of the graphs of parametric equations by computing their arc length.

Recall in Section 10.1 we found the arc length of the graph of a function, from to , to be

We can use this equation and convert it to the parametric equation context. Letting and , we know that . Suppose that , and calculate the differential of :

Starting with the arc length formula above, consider:

Note the new bounds (no longer “” bounds, but “” bounds). They are found by finding and such that and . This formula holds even when isn’t positive and we restate it as a theorem.

Theorem 10.3.1 Arc Length of Parametric Curves

Let and be parametric equations with and continuous on some open interval containing and on which the graph traces itself only once. The arc length of the graph, from to , is

As before, these integrals are often not easy to compute. We start with a simple example, then give another where we approximate the solution.

Example 10.3.7 Arc Length of a Circle

Find the arc length of the circle parameterized by , on .

SolutionBy direct application of Theorem 10.3.1, we have

| Apply the Pythagorean Theorem. | ||||

This should make sense; we know from geometry that the circumference of a circle with radius 3 is ; since we are finding the arc length of of a circle, the arc length is .

Example 10.3.8 Arc Length of a Parametric Curve

The graph of the parametric equations , crosses itself as shown in Figure 10.3.6, forming a “teardrop.” Find the arc length of the teardrop. ††margin: Figure 10.3.6: A graph of the parametric equations in Example 10.3.8, where the arc length of the teardrop is calculated. Λ

SolutionWe can see by the parameterizations of and that when , and . This means we’ll integrate from to . Applying Theorem 10.3.1, we have

Unfortunately, the integrand does not have an antiderivative expressible by elementary functions. We turn to numerical integration to approximate its value. Using 4 subintervals, Simpson’s Rule approximates the value of the integral as . Using a computer, more subintervals are easy to employ, and gives a value of . Increasing shows that this value is stable and a good approximation of the actual value.

Surface Area of a Solid of Revolution

Related to the formula for finding arc length is the formula for finding surface area. We can adapt the formula found in Key Idea 10.1.2 from Section 10.1 in a similar way as done to produce the formula for arc length done before.

Key Idea 10.3.4 Surface Area of a Solid of Revolution

Consider the graph of the parametric equations and , where and are continuous on an open interval containing and on which the graph does not cross itself.

-

(a)

The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph about the -axis is (where on ):

-

(b)

The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph about the -axis is (where on ):

(fullscreen) Figure 10.3.7: Rotating a teardrop shape about the -axis in Example 10.3.9. Λ

Example 10.3.9 Surface Area of a Solid of Revolution

Consider the teardrop shape formed by the parametric equations , as seen in Example 10.3.8. Find the surface area if this shape is rotated about the -axis, as shown in Figure 10.3.7.

SolutionThe teardrop shape is formed between and . Using Key Idea 10.3.4, we see we need for on , and this is not the case. To fix this, we simplify replace with , which flips the whole graph about the -axis (and does not change the surface area of the resulting solid). The surface area is:

Once again we arrive at an integral that we cannot compute in terms of elementary functions. Using Simpson’s Rule with , we find the area to be . Using larger values of shows this is accurate to 2 places after the decimal.

After defining a new way of creating curves in the plane, in this section we have applied calculus techniques to the parametric equation defining these curves to study their properties. In the next section, we define another way of forming curves in the plane. To do so, we create a new coordinate system, called polar coordinates, that identifies points in the plane in a manner different than from measuring distances from the - and - axes.

Exercises 10.3

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

T/F: Given parametric equations and , , as long as .

-

2.

Given parametric equations and , the derivative as given in Key Idea 10.3.1 is a function of ?

-

3.

T/F: Given parametric equations and , to find , one simply computes

-

4.

T/F: If at , then the normal line to the curve at is a vertical line.

Problems

In Exercises 5–12., parametric equations for a curve are given.

-

(a)

Find .

-

(b)

Find the equations of the tangent and normal line(s) at the point(s) given.

-

(c)

Sketch the graph of the parametric functions along with the found tangent and normal lines.

-

5.

, ;

-

6.

, ;

-

7.

, ;

-

8.

, ; and

-

9.

, on ;

-

10.

, on ;

-

11.

, on ;

-

12.

, ;

In Exercises 13–20., find -values where the curve defined by the given parametric equations has horizontal or vertical tangent lines. Note: these are the same equations as in Exercises 5.–12..

-

13.

,

-

14.

,

-

15.

,

-

16.

,

-

17.

, on

-

18.

, on

-

19.

, on

-

20.

, on

In Exercises 21–24., find where the graph of the given parametric equations is not smooth, then find .

-

21.

,

-

22.

,

-

23.

,

-

24.

,

In Exercises 25–32., parametric equations for a curve are given. Find , then determine the intervals on which the graph of the curve is concave up/down. Note: these are the same equations as in Exercises 5.–12..

-

25.

,

-

26.

,

-

27.

,

-

28.

,

-

29.

, on

-

30.

, on

-

31.

, on

-

32.

,

In Exercises 33–40., find the arc length of the graph of the parametric equations on the given interval(s).

-

33.

, on

-

34.

, on and

-

35.

, on

-

36.

, on

-

37.

, on

-

38.

, on

-

39.

, on

-

40.

, on

In Exercises 41–44., numerically approximate the given arc length.

-

41.

Approximate the arc length of one petal of the rose curve , using Simpson’s Rule and .

-

42.

Approximate the arc length of the “bow tie curve” , using Simpson’s Rule and .

-

43.

Approximate the arc length of the parabola , on using Simpson’s Rule and .

-

44.

A common approximate of the circumference of an ellipse given by , is . Use this formula to approximate the circumference of , and compare this to the approximation given by Simpson’s Rule and .

In Exercises 45–50., a solid of revolution is described. Find or approximate its surface area as specified.

-

45.

Find the surface area of the sphere formed by rotating the circle , about: (a) the -axis and (b) the -axis.

-

46.

Find the surface area of the torus (or “donut”) formed by rotating the circle , about the -axis.

-

47.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by rotating the curve , on about the axis

-

48.

Find the surface area of the solid formed by rotating the curve , on about the axis

-

49.

Approximate the surface area of the solid formed by rotating the “upper right half” of the bow tie curve , on about the -axis, using Simpson’s Rule and .

-

50.

Approximate the surface area of the solid formed by rotating the one petal of the rose curve , on about the -axis, using Simpson’s Rule and .

-

51.

Find the area under the curve given by the parametric equations , , for . Subtract this area from the area of an appropriate triangle to verify the shaded area in the bottom graph of Figure 7.4.1.