15.6 Surface Integrals

Consider a smooth surface that represents a thin sheet of metal. How could we find the mass of this metallic object?

If the density of this object is constant, then we can find mass via “mass density surface area,” and we could compute the surface area using the techniques of the previous section.

What if the density were not constant, but variable, described by a function ? We can describe the mass using our general integration techniques as

where represents “a little bit of mass.” That is, to find the total mass of the object, sum up lots of little masses over the surface.

How do we find the “little bit of mass” ? On a small portion of the surface with surface area , the density is approximately constant, hence . As we use limits to shrink the size of to 0, we get ; that is, a little bit of mass is equal to a density times a small amount of surface area. Thus the total mass of the thin sheet is

| (15.3) |

To evaluate the above integral, we would seek , a smooth parameterization of over a region of the - plane. The density would become a function of and , and we would integrate

The integral in Equation (15.3) is a specific example of a more general construction defined below.

Definition 15.6.1 Surface Integral

Let be a continuous function defined on a surface . The surface integral of on is

Surface integrals can be used to measure a variety of quantities beyond mass. If measures the static charge density at a point, then the surface integral will compute the total static charge of the sheet. If measures the amount of fluid passing through a screen (represented by ) at a point, then the surface integral gives the total amount of fluid going through the screen.

Watch the video:

Ex: Evaluate a Surface Integral (Parametric Surface — Helicoid) from https://youtu.be/pAWLCFYsrVs

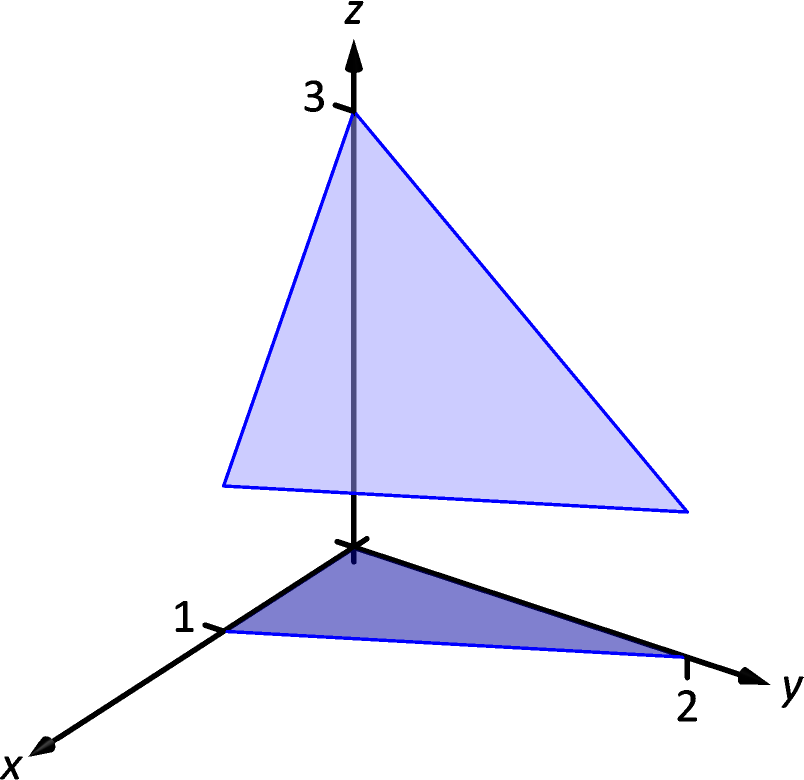

Figure 15.6.1: The surface whose mass is computed in Example 15.6.1.

Figure 15.6.1: The surface whose mass is computed in Example 15.6.1.

Example 15.6.1 Finding the mass of a thin sheet

Find the mass of a thin sheet modeled by the plane over the triangular region of the - plane bounded by the coordinate axes and the line , as shown in Figure 15.6.1, with density function , where all distances are measured in cm and the density is given as gm/cm.

SolutionWe begin by parameterizing the planar surface . Using the techniques of the previous section, we can let and , where and . Solving for in the equation of the plane, we have , hence , giving the parameterization .

We need , so we need to compute , and the norm of their cross product. We leave it to the reader to confirm the following:

We need to be careful to not “simplify” as ; rather, it is . In this example, is bounded by , and on this interval . Thus .

The density is given as a function of , and , for which we’ll substitute the corresponding components of (with the slight abuse of notation that we used in previous sections):

Thus the mass of the sheet is:

Flux

Let a surface lie within a vector field . One is often interested in measuring the flux of across ; that is, measuring “how much of the vector field passes across .” For instance, if represents the velocity field of moving air and represents the shape of an air filter, the flux will measure how much air is passing through the filter per unit time.

As flux measures the amount of passing across , we need to find the “amount of orthogonal to .” Similar to our measure of flux in the plane, this is equal to , where is a unit vector normal to at a point. We now consider how to find .

Given a smooth parameterization of , the work in the previous section showing the development of our method of computing surface area also shows that and are tangent to at . Thus is orthogonal to , and we let

which is a unit vector normal to at .

The measurement of flux across a surface is a surface integral; that is, to measure total flux we sum the product of times a small amount of surface area: .

A nice thing happens with the actual computation of flux: the terms go away. Consider:

| Flux | |||

The above only makes sense if is orientable; the normal vectors must vary continuously across . We assume that does vary continuously. (If the parameterization of is smooth, then our above definition of will vary continuously.)

Definition 15.6.2 Flux over a surface

Let be a vector field with continuous components defined on an orientable surface with normal vector . The flux of across is

If is parameterized by , which is smooth on its domain , then

Since is orientable, we adopt the convention of saying one passes from the “back” side of to the “front” side when moving across the surface parallel to the direction of . Also, when is closed, it is natural to speak of the regions of space “inside” and “outside” . We also adopt the convention that when is a closed surface, should point to the outside of . If points inside , use instead.

When the computation of flux is positive, it means that the field is moving from the back side of to the front side; when flux is negative, it means the field is moving opposite the direction of , and is moving from the front of to the back. When is not closed, there is not a “right” and “wrong” direction in which should point, but one should be mindful of its direction to make full sense of the flux computation.

We demonstrate the computation of flux, and its interpretation, in the following examples.

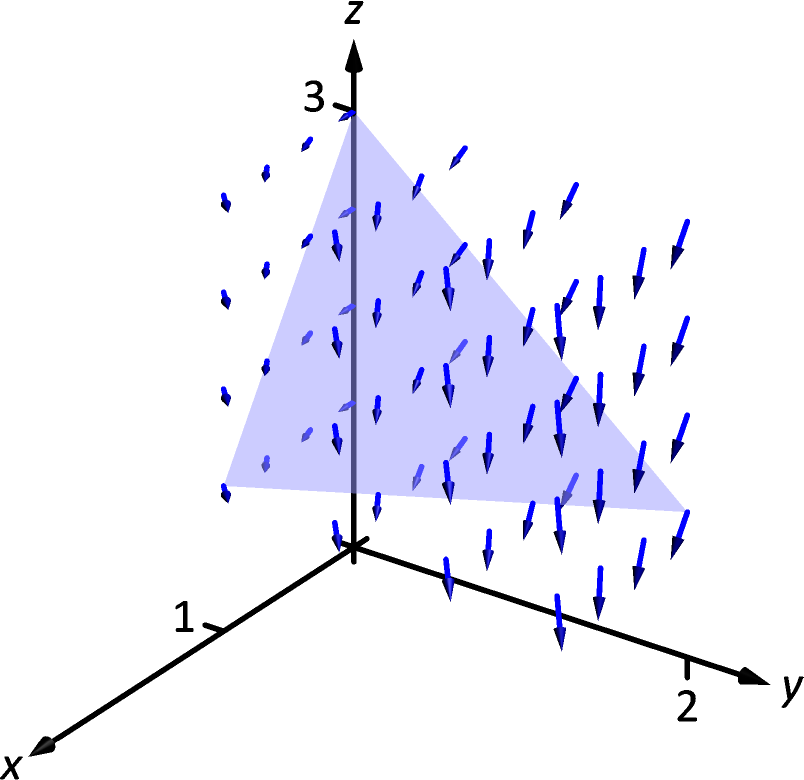

Figure 15.6.2: The surface and vector field used in Example 15.6.2.

Figure 15.6.2: The surface and vector field used in Example 15.6.2.

Example 15.6.2 Finding flux across a surface

Let be the surface given in Example 15.6.1, where is parameterized by on , , and let , as shown in Figure 15.6.2. Find the flux of across .

SolutionUsing our work from the previous example, we have . We also need .

Thus the flux of across is:

| Flux | |||

To make full use of this numeric answer, we need to know the direction in which the field is passing across . The graph in Figure 15.6.2 helps, but we need a method that is not dependent on a graph.

Pick a point in the interior of and consider . For instance, choose and look at . This vector has positive , and components. Generally speaking, one has some idea of what the surface looks like, as that surface is for some reason important. In our case, we know is a plane with -intercept of . Knowing and the flux measurement of positive , we know that the field must be passing from “behind” , i.e., the side the origin is on, to the “front” of .

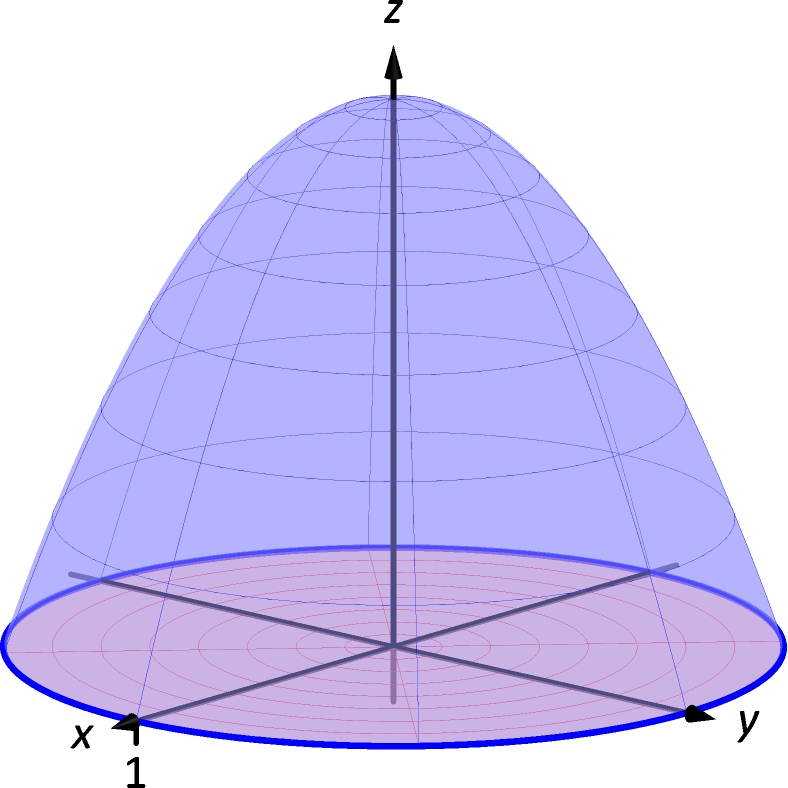

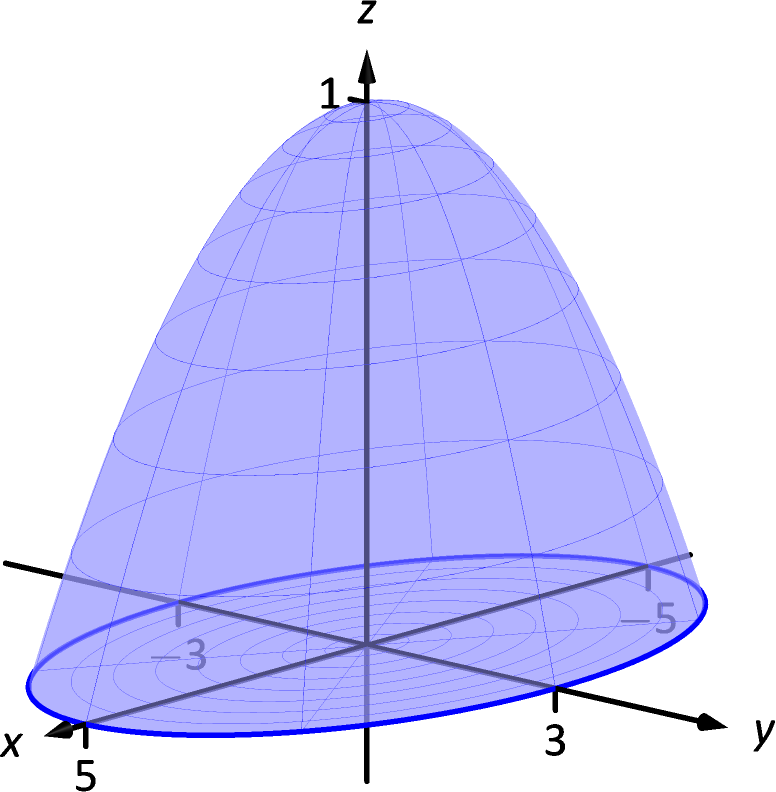

Figure 15.6.3: The surfaces used in Example 15.6.3.

Figure 15.6.3: The surfaces used in Example 15.6.3.

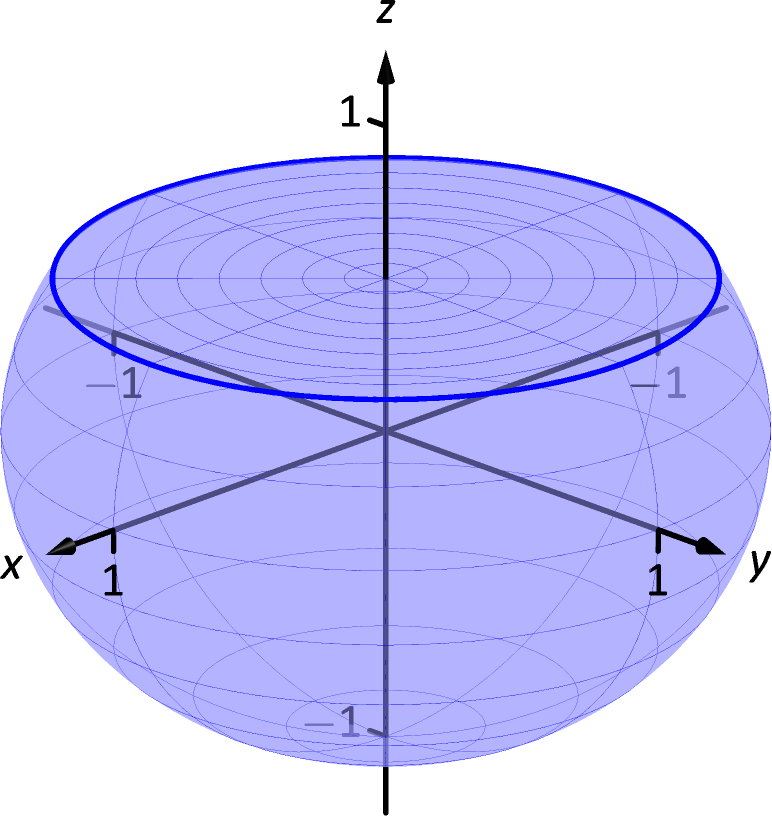

Example 15.6.3 Flux across surfaces with shared boundaries

Let be the unit disk in the - plane, and let be the paraboloid , for , as graphed in Figure 15.6.3. Note how these two surfaces each have the unit circle as a boundary.

Let and . Using normal vectors for each surface that point “upward,” i.e., with a positive -component, find the flux of each field across each surface.

SolutionWe begin by parameterizing each surface.

The boundary of the unit disk in the - plane is the unit circle, which can be described with , . To obtain the interior of the circle as well, we can scale by , giving

As the boundary of is also the unit circle, the and components of will be the same as those of ; we just need a different component. With , we have

where and .

We now compute the normal vectors and .

For : , , so

As this vector has a negative -component, we instead use

Similarly, : , , so

Again, this normal vector has a negative -component so we use

We are now set to compute flux. Over field :

These two results are equal and positive. Each are positive because both normal vectors are pointing in the positive -directions, as does . As the field passes through each surface in the direction of their normal vectors, the flux is measured as positive.

We can also intuitively understand why the results are equal. Consider to represent the flow of air, and let each surface represent a filter. Since is constant, and moving “straight up,” it makes sense that all air passing through also passes through , and vice-versa.

If we treated the surfaces as creating one piecewise-smooth surface , we would find the total flux across by finding the flux across each piece, being sure that each normal vector pointed to the outside of the closed surface. Above, does not point outside the surface, though does. We would instead want to use in our computation. We would then find that the flux across is , and hence the total flux across is . (As is a special number, we should wonder if this answer has special significance. It does, which is briefly discussed following this example and will be more fully developed in the next section.)

We now compute the flux across each surface with :

| Over , Therefore, | ||||

| Over , Therefore, | ||||

This time the measurements of flux differ. Over , the field is just , hence there is no flux. Over , the flux is again positive as points in the positive direction over , as does .

In the previous example, the surfaces and form a closed surface that is piecewise smooth. That the measurement of flux across each surface was the same for some fields (and not for others) is reminiscent of a result from Section 15.4, where we measured flux across curves. The quick answer to why the flux was the same when considering is that . In the next section, we’ll see the second part of the Divergence Theorem which will more fully explain this occurrence. We will also explore Stokes’ Theorem, the spatial analogue to Green’s Theorem.

In this chapter, we’ve introduced four new types of integrals, which we gather in Key Idea 15.6.1.

Key Idea 15.6.1 Integrating Parameterized Curves and Surfaces

| parameterizes a curve | parameterizes a surface | |

|---|---|---|

| scalar line integral: | scalar surface integral: | |

| vector line integral: | vector surface integral: |

Exercises 15.6

Terms and Concepts

-

1.

In the plane, flux is a measurement of how much of the vector field passes across a ; in space, flux is a measurement of how much of the vector field passes across a .

-

2.

When computing flux, what does it mean when the result is a negative number?

-

3.

When is a closed surface, we choose the normal vector so that it points to the of the surface.

-

4.

If is a plane, and is always parallel to , then the flux of across will be .

Problems

In Exercises 5–6, a surface that represents a thin sheet of material with density is given. Find the mass of each thin sheet.

-

5.

is the plane on , , with .

-

6.

is the unit sphere, with .

In Exercises 7–16, a surface and a vector field are given. Compute the flux of across . (If is not a closed surface, choose so that it has a positive -component, unless otherwise indicated.)

-

7.

is the plane on , ; .

-

8.

is the plane over the triangle with vertices at , and ; .

-

9.

is the paraboloid over the unit disk; .

-

10.

is the unit sphere; .

-

11.

is the square in space with corners at , , and (choose such that it has a positive -component); .

-

12.

is the disk in the - plane with radius 1, centered at (choose such that it has a positive -component); .

-

13.

is the closed surface composed of , whose boundary is the ellipse in the - plane described by and , part of the elliptical paraboloid (see graph); .

-

14.

is the closed surface composed of , part of the unit sphere and , part of the plane (see graph); .

-

15.

is boundary of the solid cube ; . Note that there will be a different outward unit normal vector to each of the six faces of the cube.

-

16.

is the part of the plane with , , and , with the outward unit normal pointing in the positive direction; .